There are topics that everyone knows exist, yet no one really talks about them out loud. In the Arab world, prostitution is one of those realities that live in whispers, behind closed doors, in the cracks of societies that hold faith and family above everything else. I have spent enough time in this region to see that behind the headlines and the moral outrage lies a world far more complex than anyone dares to admit. It’s a story of survival, contradiction, faith, and quiet rebellion one that tells as much about society as it does about the people living in its shadows.

The Uncomfortable Intersection of Law and Religion

In most Arab countries, the law and religion are deeply intertwined. Islam, in all its interpretations, is clear about sex outside marriage: it’s haram forbidden. And because Sharia forms the moral and often legal backbone of these societies, prostitution is criminalized almost everywhere. Yet, reality never obeys law as neatly as legislators wish it did.

In places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, or Kuwait, the laws are absolute. The punishments are severe, and the mere accusation can destroy lives long before any court case is heard. In Egypt, Morocco, or Tunisia, the laws are also strict, but enforcement varies depending on who you are, where you are, and how visible your actions become. It’s one of those open secrets everyone knows about yet everyone pretends doesn’t exist.

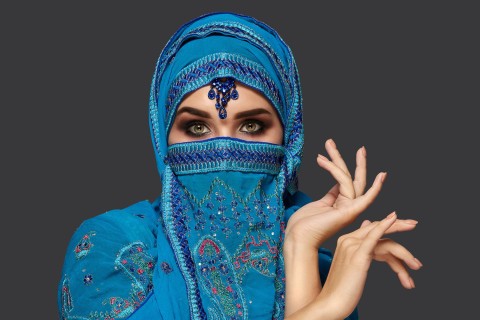

Behind the Veil of Faith and Morality

Religion here is not just a private matter; it’s a public identity. To be Arab, for many, is to be Muslim and to be a good Muslim is to uphold family, modesty, and virtue. That leaves very little space for women who sell sex, or for the men who buy it. Yet both exist, and they coexist with faith in a strange, silent tension.

Many clients are married men who pray five times a day and genuinely believe they are good believers. Many sex workers themselves are women who still hold on to their faith, praying quietly before or after they meet a client, asking for forgiveness and protection. That contradiction is rarely spoken of, but it exists everywhere in small apartments in Cairo, in hotel rooms in Dubai, in alleyways of Casablanca. Faith doesn’t disappear because someone breaks a rule; it often becomes even stronger when guilt lives beside it.

The Foreign Face of a Local Secret

When people in the Arab world talk about prostitution if they talk about it at all they often imagine foreign women. And to a large extent, they’re right. In cities like Dubai, Doha, Manama, and Beirut, many of the women who sell sex come from elsewhere: Eastern Europe, the Philippines, Thailand, Ethiopia, Morocco. They come chasing opportunities that were promised as domestic work, hostess jobs, or modeling gigs, only to find themselves trapped in debt, dependency, or fear.

But not all of them are trafficked victims, and not all are powerless. Some women choose this path as a way to make money, to send remittances home, or simply to survive in a world where legal work for women, especially foreign women, is scarce. Their lives exist in a delicate balance between visibility and danger. In the Gulf, police crackdowns come and go in waves, but as long as demand exists and it does, quietly, consistently supply finds a way.

The Hidden Arab Women

There’s another side that rarely makes headlines: the local women. In Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, and even parts of Jordan or Lebanon, there are women born and raised within these societies who also work as sex workers. Most of them never call it prostitution. They describe it as companionship, arrangement, temporary marriage, or even “helping a friend.” Language softens what law condemns.

For some, especially in rural areas, it’s a matter of survival. A single mother feeding her children, a divorced woman rejected by her family, or a university student paying tuition each story carries its own heartbreak. These women live in permanent secrecy, often renting apartments under false names, trusting only a handful of regular clients, and fearing exposure more than anything else. In the eyes of society, being known as a prostitute can mean the end of everything: family ties, reputation, and even safety.

The Male Clients No One Talks About

While prostitution in the Arab world is often framed as a women’s issue, the other half of the story the clients remains largely untold. They come from every social class. Some are wealthy businessmen who can afford discretion and luxury. Others are migrant workers themselves, lonely, far from home, and craving touch more than sex. Some are teenagers experimenting in secret. Many are married men looking for what they believe is a harmless escape.

What unites them is the silence. Nobody admits to being a client. Nobody talks about desire in societies that don’t even teach young people how to understand it. Sex is expected to exist only within marriage, yet the realities of modern life long work hours, migration, economic stress, delayed marriages have made that ideal increasingly distant. Prostitution fills that gap, even if it’s never named.

Between Hypocrisy and Compassion

What struck me most while researching this subject was not the existence of prostitution itself, but the contradictions surrounding it. In public, governments condemn it, religious leaders denounce it, and families pretend it’s not happening. Yet behind closed doors, the same societies quietly tolerate it so long as it remains hidden, discreet, and out of sight.

There is a deep cultural hypocrisy that runs through it all. Everyone agrees that prostitution is shameful. But the shame is never evenly distributed. The women carry the full weight of it. Men, on the other hand, often walk away untouched, forgiven, invisible.

Still, there are small signs of change. Across North Africa and the Middle East, NGOs and informal networks have begun offering health services, counseling, and legal aid to sex workers often at great risk. They cannot operate openly, so they disguise their work as health outreach or community care. These efforts are driven less by ideology and more by empathy the recognition that judgment solves nothing, while compassion might at least protect lives.

When Tourism and Globalization Collide

In some places, especially coastal and tourist-heavy cities like Marrakech, Cairo, or Beirut, the lines between sex work and entertainment blur even more. Nightlife scenes thrive on glamour, foreign money, and the illusion of freedom. For Western visitors, the region’s conservatism adds an exotic layer of thrill; for locals, it’s an outlet hidden under the glow of tourism.

The rise of social media and dating apps has made everything easier to arrange and harder to regulate. A few clicks can connect a client to a companion without ever saying the word “sex.” Everything is coded, everything discreet. Instagram profiles with suggestive photos, WhatsApp numbers exchanged quietly it’s all there, digital and invisible at the same time.

The Emotional Weight Nobody Sees

What often gets lost in policy debates or moral sermons is the human cost. Many of the women I’ve spoken to described an inner conflict that eats at them daily the struggle between faith and survival, shame and strength. They live double lives, pretending to be someone else during the day, and slipping into another skin at night.

Loneliness is a constant companion. So is fear. Fear of arrest, fear of exposure, fear of judgment. But amid all that, there’s also resilience a quiet, stubborn will to keep going. These women are not faceless statistics. They laugh, they love, they dream. Some hope to save enough to start over, others simply want to make it to next week. Every one of them carries a story society refuses to hear.

Looking Beyond Judgment

To talk about prostitution in the Arab world is to walk on a tightrope between respect for religion and honesty about human behavior. It’s easy to moralize from a distance. It’s harder to look at the faces behind the moral panic and see real people, shaped by poverty, patriarchy, migration, and sometimes by sheer bad luck.

The question is not whether prostitution should be accepted it’s whether societies can find the courage to address it with humanity instead of denial. Ignoring it hasn’t made it go away. Criminalizing it hasn’t stopped exploitation. Maybe the first step is simply talking about it without turning away.

Faith, Dignity, and Change

I’ve often thought that the teachings of Islam at their core are about mercy, justice, and compassion. Those values don’t disappear when someone sins or struggles. If anything, that’s when they matter most. Perhaps one day, conversations around prostitution in the Arab world will move away from condemnation and toward care.

That doesn’t mean moral acceptance. It means seeing people as more than the labels society gives them. It means acknowledging that every human being, even the ones we’d rather not think about, deserves dignity. Until that happens, prostitution will remain what it is today hidden, condemned, but quietly alive beneath the surface of societies that are still learning how to reconcile faith with the messy reality of human need.